Unlike the alien landscapes and alternative futures of science fiction, the worlds of the zombie apocalypse are ours. They operate as allegories for the failures of government, social institutions, and the fragmentation of community. The zombie is our neighbor, the zombie is us. When he introduced the flesh-eating risen dead in 1968, George Romero became the father of the modern movie zombie. He scorned the later postmodern 'fast' versions in Zack Snyder's 2004 remake of "Dawn of the Dead" and the army-ant antics of the CGI-undead in Marc Forster's adaptation of "World War Z" (2013). While these video game-inspired variations might be great for shock-value, the frenzied pack depersonalizes the threat and losing the dread of its slow, creeping inevitability. The Fast-zombies lack the elements of satire and social critique with which Romero invested his own shuffling undead.

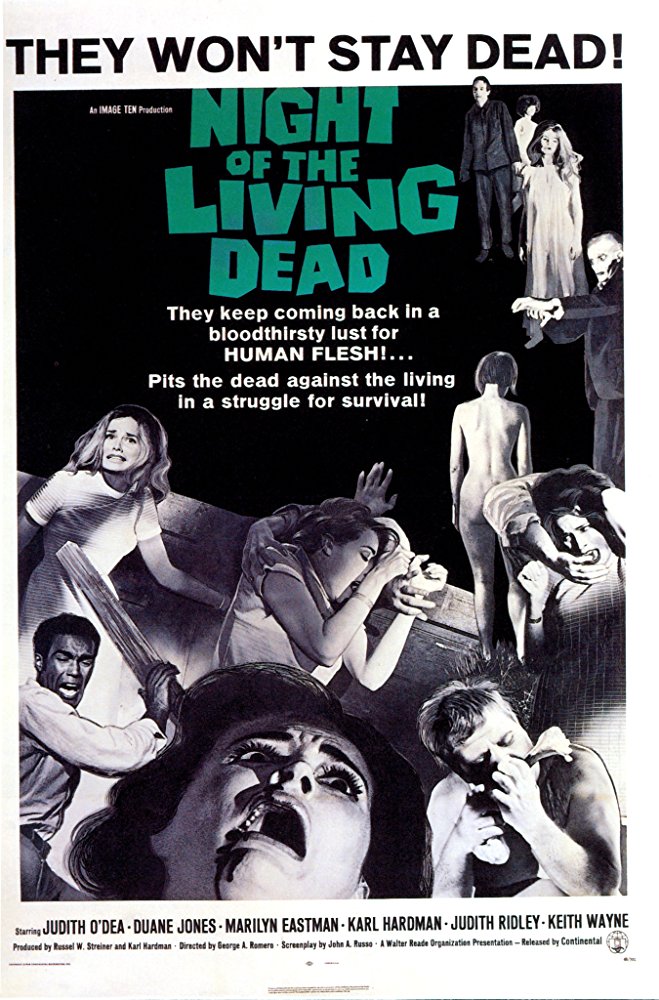

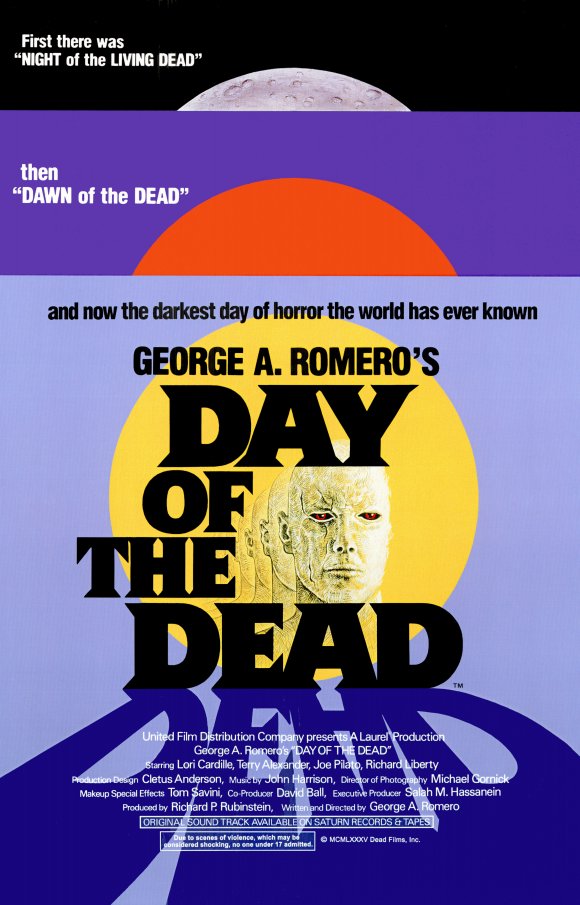

In interviews Romero talked up his use of slapstick and satire, downplaying critics who considered his work socially revolutionary or radical. However, even though he denies intent, issues of race, gender, and social class thread through all of his "Dead" films. "Night of the Living Dead" (1968) touches on a number of Vietnam-era themes, particularly tensions between race and generations, but also gesturing toward the divide between urban and rural cultures. "Dawn of the Dead" (1978) depicts police violence in the inner-city and hints toward race war, even though its overarching message is to satirize the American consumer culture. "Day of the Dead" (1985) is more nihilistic in criticizing the military-industrial complex for its short-sighted focus on victory as the odds of nuclear war increased during the first Reagan administration. The themes of his three post-9/11 movies are a less coherent: "Land of the Dead" (2005) emphasizes the gap between the corrupt rich and the rest. "Diary of the Dead" (2007) indicts the mainstream media as a tool of elites and disinformation in contrast to the revolutionary use of emerging media. "Survival of the Dead" (2009) hinges on an ideological crisis with religious overtones that splits a community in two and destroys it. Many fans andcritics divide Romero's "Dead" films into two sets because of the two decades that separate them, but this obscures the continuity of Romero's social commentary over the span of his career.

In interviews Romero talked up his use of slapstick and satire, downplaying critics who considered his work socially revolutionary or radical. However, even though he denies intent, issues of race, gender, and social class thread through all of his "Dead" films. "Night of the Living Dead" (1968) touches on a number of Vietnam-era themes, particularly tensions between race and generations, but also gesturing toward the divide between urban and rural cultures. "Dawn of the Dead" (1978) depicts police violence in the inner-city and hints toward race war, even though its overarching message is to satirize the American consumer culture. "Day of the Dead" (1985) is more nihilistic in criticizing the military-industrial complex for its short-sighted focus on victory as the odds of nuclear war increased during the first Reagan administration. The themes of his three post-9/11 movies are a less coherent: "Land of the Dead" (2005) emphasizes the gap between the corrupt rich and the rest. "Diary of the Dead" (2007) indicts the mainstream media as a tool of elites and disinformation in contrast to the revolutionary use of emerging media. "Survival of the Dead" (2009) hinges on an ideological crisis with religious overtones that splits a community in two and destroys it. Many fans andcritics divide Romero's "Dead" films into two sets because of the two decades that separate them, but this obscures the continuity of Romero's social commentary over the span of his career.

During the course of the six "Dead" films, Romero also depicts the gradual arming of America and, despite the militarization of its civil authorities, the failure of police, National Guard, or other armed forces to prevent social collapse. At the heart of most stories of the zombie apocalypse is a group of survivors. Inspired by Romero's riff on Richard Matheson's 1954 novel, "I Am Legend," these small bands, surrounded by the undead, are forced to fend for themselves as the world around them collapses into chaos. Average citizens are forced to take up arms initially todefend themselves, then to acquire supplies. As they shift from defense to acquisition, survivors become raiders. Once the authorities and military have disappeared, those with the most advanced (battlefield-grade) weapons use them to overwhelm the 'tribes' or communities who oppose them.

A county sheriff steps in to lead when state and national authorities remain confused and ineffective in "Night of the Living Dead." Sheriff McClelland tells television reporters how the undead must be fought and destroyed, knowledge gained by running the local search and destroy missions against them. However, it is also the sheriff who directs the shooting of the lone survivor of the farmhouse, Ben, a young, African-American man. Ben's execution is read by many as a lynching. Romero has stated that the script always ended this way and that it was incidental that Duane Johnson was black. Another scene aligns with television footage and newspaper photographs of police responding to marches and peaceful demonstrations during civil rights protests. Near the end of the film, state troopers deploy German Shepherds as part of zombie hunting activities, drawing comparisons to the use of police dogs against marchers in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963. The sheriff is not in uniform, and while their clothing is a mix of city and country styles, all of the riflemen hunting zombies are white. This reflects the demographics of southwest Pennsylvania, where Night was filmed, but it also underscores the imagery of racial mob violence and troubles the role of the sheriff as an elected leader and his control of the armed posse.

"Dawn of the Dead" shifts locations from an isolated, rural farmhouse first to Philadelphia, then to suburbia--the Monroeville shopping mall. "Dawn" picks up with the search and destroy teams, this time supplemented with National Guard troops and vehicles. The Guard units do not appear professional or disciplined; they stand about smoking, drinking, and taking pictures, only putting down their beers when the undead wander into the extended tailgate party. In Philadelphia, Guardsmen join the police, including their paramilitary SWAT teams, in raiding a tenement building. The lack of discipline and leadership among those invading the apartment building is a criticism that violence of Guard and police deployed to quell the the 1968 riots in cities across the nation, including Pittsburgh and Philadelphia following Martin Luther King, Jr.'s assassination. The SWAT team is also more military than police; they become so mission oriented in their pursuit to destroy the undead that they not only fail to protect the civilians, but even shoot several innocent bystanders. One member of the SWAT team begins to fire indiscriminately, killing at random until he is shot by another officer, Peter. White fear of Black Panthers patrolling Californian cities with legal weapons lead to the passage of the Mumford Act in California in 1967, restricting the open carrying of loaded weapons in public. This fear can be seen in the invasion of the apartments. Although Guardsmen, police, and the armed resistors are multi-ethnic, most of those who resisted the authorities appear black or hispanic. These armed civilians were not allowed to protect their own homes. When they try to resist their invaders with handguns and a few rifles, they are overwhelmed by machine guns and shotguns.

"Dawn of the Dead" shifts locations from an isolated, rural farmhouse first to Philadelphia, then to suburbia--the Monroeville shopping mall. "Dawn" picks up with the search and destroy teams, this time supplemented with National Guard troops and vehicles. The Guard units do not appear professional or disciplined; they stand about smoking, drinking, and taking pictures, only putting down their beers when the undead wander into the extended tailgate party. In Philadelphia, Guardsmen join the police, including their paramilitary SWAT teams, in raiding a tenement building. The lack of discipline and leadership among those invading the apartment building is a criticism that violence of Guard and police deployed to quell the the 1968 riots in cities across the nation, including Pittsburgh and Philadelphia following Martin Luther King, Jr.'s assassination. The SWAT team is also more military than police; they become so mission oriented in their pursuit to destroy the undead that they not only fail to protect the civilians, but even shoot several innocent bystanders. One member of the SWAT team begins to fire indiscriminately, killing at random until he is shot by another officer, Peter. White fear of Black Panthers patrolling Californian cities with legal weapons lead to the passage of the Mumford Act in California in 1967, restricting the open carrying of loaded weapons in public. This fear can be seen in the invasion of the apartments. Although Guardsmen, police, and the armed resistors are multi-ethnic, most of those who resisted the authorities appear black or hispanic. These armed civilians were not allowed to protect their own homes. When they try to resist their invaders with handguns and a few rifles, they are overwhelmed by machine guns and shotguns.

Romero's depiction of militarized police is less negative when they protect their community. When the former SWAT team members, Peter and Roger, join Stephen and Francine to create the survivors sanctuary in Monroeville Mall, they create a new community. The former-SWAT members use police training and experience with weapons to strengthen the group. Peter and Roger outline and execute the plan to secure the mall using trucks, and then to clear the installation of the undead. Even though he is bitten and knows he is dying, Roger insists on helping the others with their search, destroy, and secure mission. Peter becomes an instructor, stepping in to train Francine to load and shoot a rifle. Peter is a professional and sharpshooter, and thus more competent than Stephen. Unfortunately, their numbers are too few to defend the mall from the biker gang, leading to Stephen's death. Peter is only saved because Francine has been taught how to fly the helicopter, completing the reversal of social and gender roles. In strengthening and defending their 'family,' the former police officers return to their first mission, to serve and protect, rather than policing populations and enforcing policy.

"Night" and "Dawn" show the confusion and indecision of the federal government and state leaders through media reports, but in "Day of the Dead" Romero illustrates the apocalyptic failure of military leadership. One key feature of his post-apocalypse is the breakdown in military discipline as former military personnel become better-armed bandits who prey on other survivors. Romero's criticism draws on American social discourse in the wake of Vietnam, one that talked about the corruption of superior's, civil and military, and touches on issues such as PTSD, substance abuse, and general public distrust of veterans. The central conflict in Day is between the civilian science team and a military unit. Although it begins under the control of Dr. Logan, he cedes authority to Captain Rhodes when he becomes obsessive about his experiments. Under Rhodes, the Army detachment loses cohesion, discipline and becomes a danger to the civilian contractors and scientists. The men under Rhodes's command become sloppy and careless when handling the zombie test subjects, leading to the death of one and mutilation of another. The four enlisted men descend into alcoholism, fight amongst themselves, and sexually harass the female scientist, Sarah. Rhodes eventually turns on everyone, first threatening summary executions, later killing both Logan and the science technician Fisher, before forcing the remaining civilians into the zombie holding pen. The civilians escape the pen, and use a helicopter to find sanctuary. All of the military personnel are destroyed by zombies, ending the mission.

"Night" and "Dawn" show the confusion and indecision of the federal government and state leaders through media reports, but in "Day of the Dead" Romero illustrates the apocalyptic failure of military leadership. One key feature of his post-apocalypse is the breakdown in military discipline as former military personnel become better-armed bandits who prey on other survivors. Romero's criticism draws on American social discourse in the wake of Vietnam, one that talked about the corruption of superior's, civil and military, and touches on issues such as PTSD, substance abuse, and general public distrust of veterans. The central conflict in Day is between the civilian science team and a military unit. Although it begins under the control of Dr. Logan, he cedes authority to Captain Rhodes when he becomes obsessive about his experiments. Under Rhodes, the Army detachment loses cohesion, discipline and becomes a danger to the civilian contractors and scientists. The men under Rhodes's command become sloppy and careless when handling the zombie test subjects, leading to the death of one and mutilation of another. The four enlisted men descend into alcoholism, fight amongst themselves, and sexually harass the female scientist, Sarah. Rhodes eventually turns on everyone, first threatening summary executions, later killing both Logan and the science technician Fisher, before forcing the remaining civilians into the zombie holding pen. The civilians escape the pen, and use a helicopter to find sanctuary. All of the military personnel are destroyed by zombies, ending the mission.

The apocalypse cannot occur unless the armed forces fail to prevent an attack on national institutions and civil authorities fail to preserve order and protect citizens. Romero's critique is directed domestically, toward the growing separation of the police from their communities as they become regarded as outsiders, enforcers of the elites, and predators. In "Night" Ben is killed because he is not recognized as a living human by the sheriff or his deputized gunman. Peter and Francine escape in "Dawn" because their community had reintegrated civilians and police. But "Day" has no community; the military is always separate, hostility becomes open warfare. A standoff between armed civilians and Army personnel happens twice, the second ending when Rhodes executes the unarmed Fisher to force the remaining civilian, John, to turn over his weapons. This perverts martial law, permanently destroying the authority of the military to command the mission. At this point the Army personnel have lost institutional affiliation not with the collapse of the government, but by becoming renegades and murderers, a point further addressed in our next blog which considers this theme in the final three films of Romero's Dead series.

Internet Movie Database (N.D.). 'Night of the Living Dead Poster' (1968)

Internet Movie Database (N.D.). 'Dawn of the Dead Poster' (1978)

Internet Movie Database (N.D.). 'Day of the Dead Poster' (1985)

by Rikk Mulligan, Digital Scholarship Strategist