As wonderful as the Posner Memorial Collection is, it’s hard to avoid the fact that most books in the collection are European. For my next blog post, I wanted to highlight some of the diversity within the collection and branch out from the standard narrative of the history of science, centered on Western Europe. I settled on The Kasîdah, a poem written by the Iranian Sufi mystic Hâjî Abdû el-Yezdî. Abdû’s poem was translated by Richard Francis Burton, an English orientalist and explorer, and published in 1880. What we know about Abdû is given in a long note by Burton at the end of the poem: he was born in central Iran, studied literature in many languages, and met Burton during the latter’s travels in British India. It’s a shame that more biographical information on Abdû is not available, but even these fragmentary glimpses of one of the few non-European contributors to the collection are worth celebrating.

…At least, that’s the story Burton told. In reality, most of that isn’t true. The Kasîdah was not a translated work of Iranian poetry: Burton himself wrote it. The character Abdû never existed.

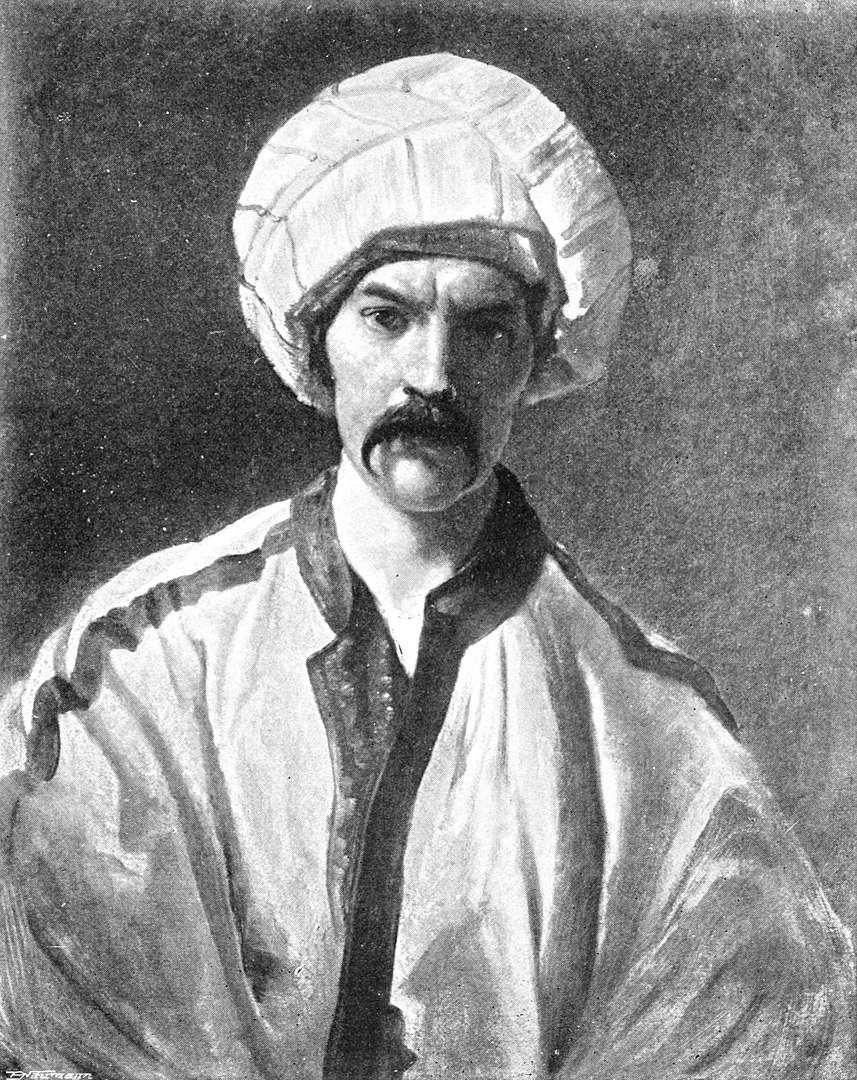

Richard Burton, unlike Abdû, was very real, and one of the strangest personalities of Victorian England. He is most famous for disguising himself as a Muslim traveller and joining the pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina. Burton was not the first non-Muslim European to complete the hajj, but his journey was probably the most famous. He traveled extensively around the Middle East, Africa, and British India, claiming to speak over 20 languages by the end of his life. Burton’s historical legacy is complex: different commenters have called him imperialist, anti-imperialist, racist, culturally relativist, misogynistic, sexually libertine, anti-semitic, or gay. Edward Said praised Burton for his deep knowledge and genuine curiosity about Islamic culture, and yet claimed that he was ultimately an agent of the British Empire, able to view Asia only from a position of supremacy.

After falling down this Burton rabbit hole, I had to know: how did readers of The Kasîdah feel about this? Did they realize that the poem was not written by a Sufi mystic, and did they care?

Here is what we can know for sure: The Kasîdah was originally published in 1880. Burton died in 1890. In 1893, his widow, Isabel Burton, published a biography of Richard and revealed that he was the poem’s author. A second edition of The Kasîdah was published the next year and made the correct authorship clear. Google Books and Proquest are not complete records of everything that has been published, but based on those databases, newspapers and magazines paid much more attention to the poem after the 1894 edition was published. So, unfortunately it’s hard to find any commenters who believed they were reacting to an authentic work of Iranian literature.

But the post-1894 reactions are interesting in themselves. I haven’t been able to find a single reviewer of The Kasîdah who was upset at Burton’s deception. No one accused him of being a liar, and no one considered the poem worth any less for being inauthentic. Most reviews were positive, praising Burton for his deep spiritual insights, or even comparing him to the famous Iranian poet Omar Khayyam. One reviewer put it this way: “Oriental imagery couched in sublime language, pearls of thought rendered immortal by their beautiful setting.”

What do we make of this? Burton was writing during an era of growing imperialism and global trade, when European readers were hungry for stories from strange, “exotic” lands. In this context, plenty of European or American entertainers became famous for their sensationalist, often inaccurate depictions of the non-Western world (think of Gilbert and Sullivan’s Mikado or Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan stories). I half suspected that Burton’s audience--more literate, philosophical, highbrow--might consider itself above such popular, unrefined works and gravitate toward authentic depictions of the world. In this view, Burton, with his deep knowledge of Islamic cultures, might as well be an authentic Iranian. Of course, he was not: The Kasîdah was a combination of Burton’s own idiosyncratic views, based on his rejection of Victorian social mores, and the knowledge of Sufism that he picked up while traveling around British India.

I began this post looking for non-European voices in the archives, and ended up finding a European reflecting his own (admittedly deeply-researched) ideas back at a European audience. Burton’s life and writings may not be the best source to learn about Islam (many better resources are available to English speakers today), but it provides a window into the strange stories of cultural exchange and domination that can be accessed through modern archives.

by Posner Curatorial Intern Jamie Leach