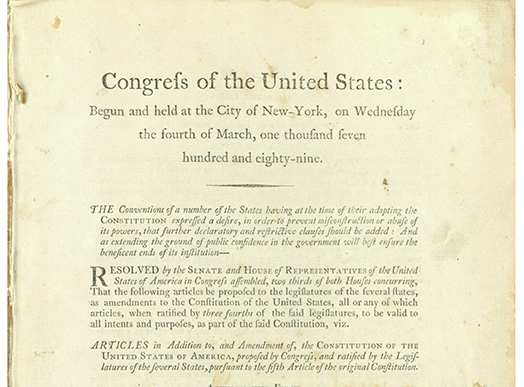

Besides its rarity, this particular printing of the Bill of Rights is significant because it was issued almost immediately after ratification. This document, in other words, represents the first time that the Bill of Rights was accorded force of law, and the first time that its ten articles appeared in print as a vital and integral part of the United States Constitution.

The Bill of Rights inhabits a strange documentary category. Its amendments are so frequently intoned and alluded to as to exist separate from any written form. It is as much a spoken creed as it is a list of rights on paper. By comparison, this country's other constitutive document, the Declaration of Independence, is far more substantial and mediated. From an early age, Americans are taught of the existence of an original Declaration: a faded piece of vellum encased inside several inches of glass. But even this ‘original' deceives. It is an imitation written by hand (‘engrossed') after a now-lost rough copy.

There are early copies of the Bill of Rights, of course. Several were engrossed in 1789 after the proposed articles were approved by Congress. These handwritten copies were distributed to the states (then only 13 in number) for debate and ratification, while the text of the proposed Bill was reprinted widely in newspapers and broadsides for a readership of curious citizens. One of these "original" engrossed copies is now displayed at the National Archives, but in comparison with the Declaration of Independence exhibited nearby, the aura of this display copy is somehow dimmer and its historical importance less immediate.

This divergence raises the question: why is the Declaration seen as a singular and treasured artifact, while the Bill of Rights lingers in the realm of non-genre?

It may have something to do with the fact that the Declaration encodes an event; it is, or was, an announcement of intent signaling the colonies' resolve to reject the perceived tyrannies of the British throne and to accept the inevitability of war. The Bill of Rights, on the other hand, is a product of compromise and legislative technicality.

More to the point, the Declaration of Independence represents America's promise ('We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal…'), while the Bill of Rights represents a deferral, and in many ways a diametric betrayal of that promise. Because of this, it is more difficult to revere, particularly in 2020.

The occasion of the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment—which guaranteed women the right to vote—offers no better reminder of the shortcomings of the original Bill of Rights: twelve articles were proposed in 1789, ten were ratified in 1792, though none of these expanded the franchise or challenged the system of chattel slavery then practiced in the United States.

Thomas Jefferson, who was responsible for commissioning the printing of the Posner Bill of Rights as Secretary of State, once observed of the Constitution: 'It is a good canvas, on which some strokes only want retouching.' The centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment demonstrates that Jefferson's words still hold, though in ways he likely never considered. We've inherited a good canvas still in need of retouching.

While Special Collections and the Posner Memorial Collection remain open by appointment only during the coronavirus pandemic, the Posner Bill of Rights can be viewed on the Libraries' Digital Collections platform.

1. 'From Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, 31 July 1788,' Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-13-02-0335. [Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 13, March–7 October 1788, ed. Julian P. Boyd. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1956, pp. 440–443.]